Massive asteroid strike 3460 million years ago proven through examining drill core in Perth.

| Date: | Monday, 13 June 2016 |

|---|

The Geological Survey of Western Australia (GSWA) has figured prominently in a scientific paper on an asteroid impact 3460 million years ago that has captured the imagination of the world’s media.

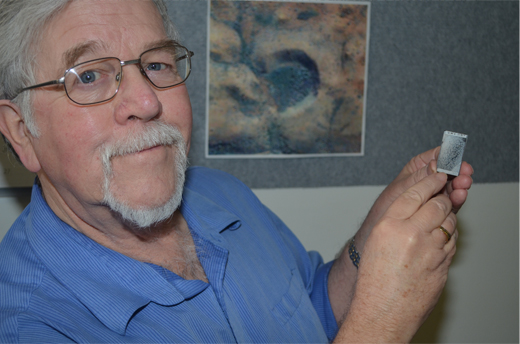

Veteran senior geoscientist Dr Arthur Hickman, who found the Hickman Crater in the Pilbara in 2007, and the paper’s lead author Dr Andrew Glikson of the Australian National University (ANU) discovered the evidence of a massive unrecorded asteroid strike while the pair were examining drill core at GSWA’s Core Library in Perth.

The asteroid is the second oldest known to have hit the Earth and one of the largest.

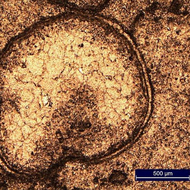

The evidence in the core, taken from a collaborative drilling project in Marble Bar in 2003, is seen as layers of tiny glass spherules similar to beads

“Finding the spherules was just the first step because we then had to prove they were formed by an asteroid impact,” Dr Hickman said.

“Scientific analysis of the spherules also involved GSWA’s Chris Kirkland (now at Curtin University) and Sandra Romano, and took over a year to complete.”

Other scientists from Curtin, Geoscience Australia, ANU, and Seoul National University, also worked on the study.

“In the end, all the evidence revealed that the Marble Bar spherules were formed by the impact of a giant asteroid between 20 to 40 km across”, Dr Hickman said.

“By comparison, the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago was quite small.

“If an asteroid 20 to 40 km across, such as Eros, the largest present asteroid, hit the Earth today it would have catastrophic effects, not only at the impact site but globally.

“In the first few seconds it would form a crater hundreds of kilometres across and tens of kilometres deep.

“It could break through Earth’s crust, resulting in massive volcanic eruptions.

“All across Earth it would trigger major earthquakes, fires, and giant tsunamis hundreds of metres high.

“The Earth would then remain in total darkness for many months and most life would be extinguished, probably all life on the surface.”

Dr Hickman said that no-one knew the site of the original impact.

“These impact spherules are formed in the atmosphere by crystallisation of the condensed rock and asteroid vapour produced by the impact and they were deposited globally, so the impact could have been anywhere on Earth,” he said.

“When an asteroid crashes into the Earth – everything sprays up and gets in the atmosphere – like volcanic dust after a big eruption.”

Dr Glikson, who has been hunting ancient asteroid impacts for more than 20 years, was drawn to the notoriously hot area west of Marble Bar ironically named North Pole because he believed impact spherules would be found in sedimentary rocks there.

However, as Dr Hickman points out, rather than braving the heat (“I’ve been there when it was 50 degrees in the shade”) and tough conditions at Marble Bar, it made more sense to drive to the suburb of Carlisle and look at the drill core.

“We couldn’t have done it without the core library,” Dr Hickman said.

“The only place to see these impact spherules is at Carlisle, because if you go to Marble Bar where the main outcrops of chert (sedimentary rock) are, the level with the spherules is not exposed.

“It probably explains why nobody has found them before, because geologists and tourists have been swarming over the chert outcrops at Marble Bar for a hundred years looking at the rocks for all sorts of reasons but never found any spherules.”

Dr Hickman, fellow GSWA senior geoscientist Dr Sandra Romano and former GSWA officer Dr Chris Kirkland, now an Associate Professor at Curtin University, worked on the paper being published in the July issue of Precambrian Research.

News of the ancient asteroid impact didn’t just excite academia, the story has gone around the globe, appearing in publications as diverse as Science Daily and the Daily Mail.